Very recently, I decided to challenge myself to read X-Men from the very beginning. I’m not sure how far I’ll get in this project, but I’m determined to keep reading until I’m so burned out on X-stuff that I just have to stop.

For the record, I’ve read a huge portion of the 21st Century X-Men already, and I’ve read most of Chris Claremont’s most important storylines from the 1970s and 1980s (I’m a big fan of Claremont’s 1980s stuff). But this time I’m starting from the very beginning (all the way back with issue #1 from 1963), and I’m going to try to do a comprehensive read this time around, including issues I’ve already read (but this time in the context of the greater over-arcing stories).

I’m also reading some of the issues of other series that tie into X-Men. Kudos to Crushing Krisis for the reading order, which helped me get my bearings (though I also used the editorial cues that pop up in various panels within the stories themselves). My goal was to read all of the older stuff in order without bothering with new material that retroactively was set in that original era, though I did end up throwing the first run of X-Men: First Class into the mix (since I own the oversized hardcover).

I’ll map out my entire reading journey at the bottom of this review, in case you want to embark on a similar reading project.

Spoiler alert

I’m talking about a comic series that’s almost 60 years old at this point. I’m going to barge through this, assuming everyone who’s reading this has either already read 1960s X-Men or just doesn’t care about the surprises it contains. Of course, it probably doesn’t matter too much, because a synopsis of these issues is probably all you need if you’re interested in learning about the formative years of the X-Men. This series was not very good in the 1960s, and Claremont’s run (beginning in the 1970s) is a much better jumping in point for potential X-fans.

So how was it?

I just have to say this upfront: The 1960s weren’t kind to the X-Men. This is generally considered to be the worst decade of the series, and I can see why. I’m just not a fan of what I refer to as “Wham-Boom-Pow” comics, and this era of X-Men is pure “Wham-Boom-Pow” villain-of-the-month silliness. I have a degree in Literature, so I generally prefer philosophical diatribes about why we fight to actually seeing the fights happen, and I would almost always rather read about the X-Men as social outcasts than as superheroes (the series will start moving in that direction once Claremont takes over in the 1970s).

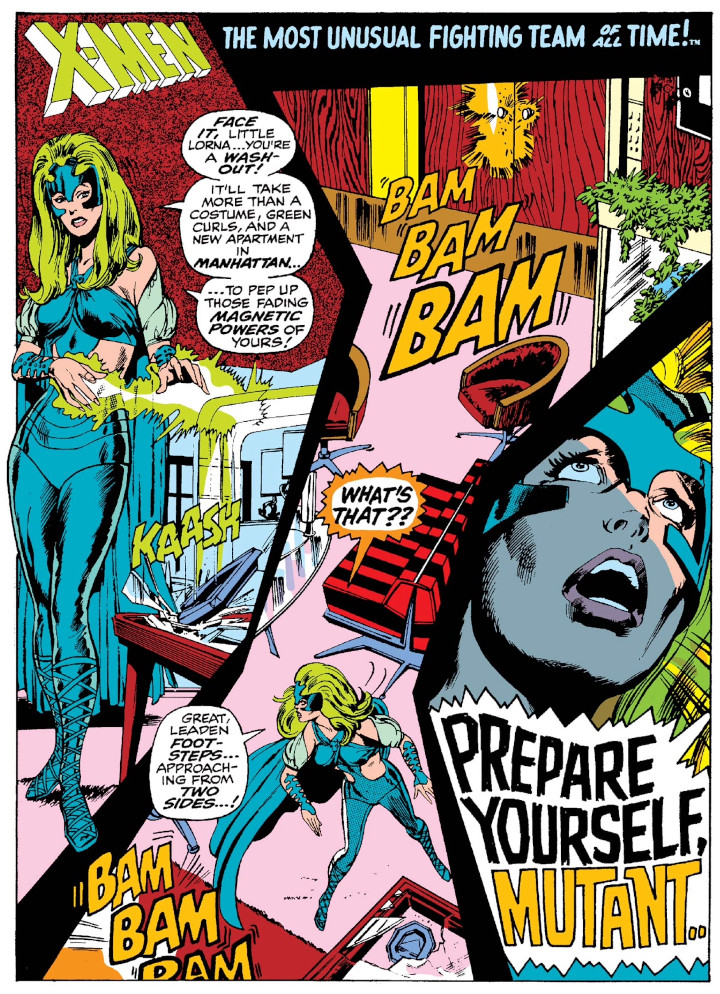

However, these early issues aren’t without their high points. It was neat to see the beginning of the team (though the origin/featurette stories that fluff out issues #38-58 were kind of a snooze-fest, in my opinion). I especially enjoyed seeing the very beginning of Alex Summers and Lorna Dane’s arcs, which continue into the Claremont years. It actually makes a lot of sense why these two characters decide to leave the team in issue #94 based on the trauma they experienced in their early adventures.

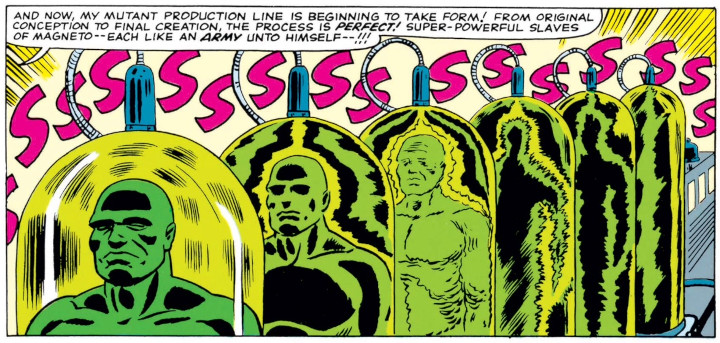

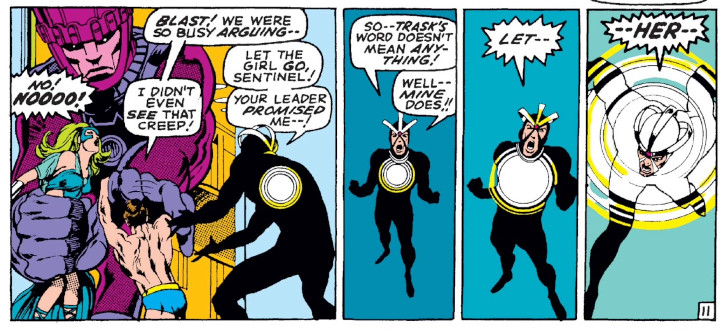

We also see some other important firsts, from the first appearance of Magneto (in issue #1) to the assembly of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (in issue #4) to the first “death” of Charles Xavier (in issue #42 — obviously, this didn’t stick). And, of course, the first story involving the Sentinels happens very early in this run (issues #14-16, with a second storyline in issue #57-59).

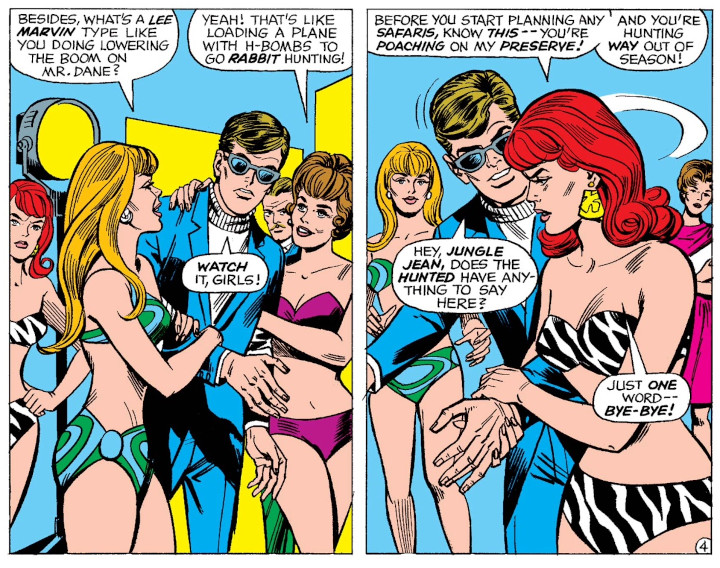

We also see the beginning of the relationship between Scott Summers and Jean Grey, though it’s handled really awkwardly. They start expressing their mutual feelings for each other via thought bubbles in issue #7, but when they start dating officially, it happens off-panel, which is casually referenced for the first time in issue #48. This is an incredibly unsatisfying payoff for a romance that was teased for more than 40 issues.

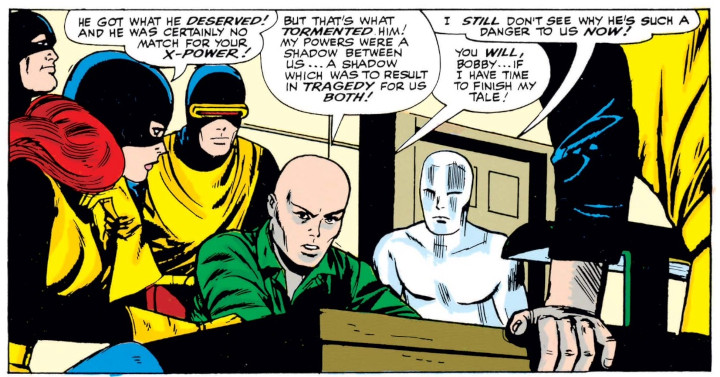

The absolute cream of this crop, though, is issue #12, “The Origin of Professor X.” This is hands-down the best issue of this entire batch, and I honestly think it’s worth reading today. In this story, the X-Men face their toughest foe yet, Juggernaut, but instead of clobbering him outright (that will happen in the next issue), they set up a series of traps to slow him down. As Juggernaut smashes through each one, getting closer and closer, Xavier tells the X-Men about his tragic childhood.

The scene shifts between the present, when Juggernaut is approaching, and flashbacks of Xavier and Cain Marko (AKA Juggernaut) as children, giving readers an insight into their tangled past (the two are stepbrothers).

This story is genuinely good, and it shows off Stan Lee’s writing chops remarkably well, something that’s simply not true of the series before this. This issue humanizes the previously mysterious Charles Xavier, and seeing him get bullied as a child brings a poignancy to the series that was lacking up until this point. This is where X-Men finally starts developing some genuinely intriguing character drama.

The tension here is balanced between the two halves of the story, with Xavier’s backstory interrupted by scenes showing the X-Men huddled around Xavier’s desk, just waiting for the inevitable moment when the Juggernaut bursts through the wall to take them all on. And Cain Marko is a force that cannot easily be stopped. This is some good stuff, and I imagine this issue served as inspiration for Claremont’s version of the X-Men in the 1970s.

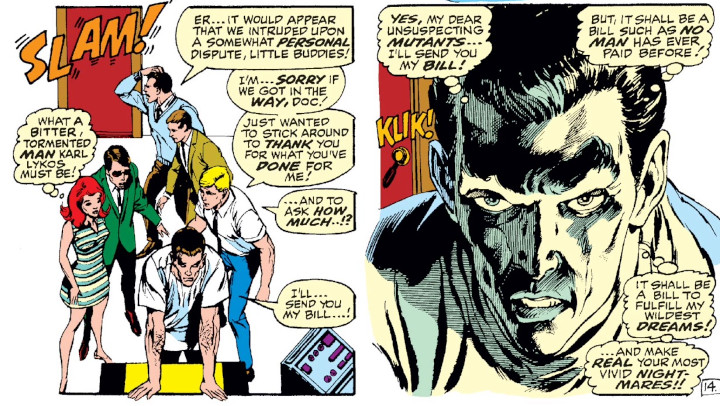

I was also surprised by how much I enjoyed Sauron’s origin story. I’ve always thought Sauron was kind of a lame villain, but I’ve been forced to rethink that opinion after reading issues #60-61 (to be fair, I’ve not read a lot of Sauron material before this). Sauron might be a giant Pteranodon dude, but he’s a conflicted one. There are two sides at war within his psyche, much like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and each side has a physical manifestation (the Pteranodon being the ultimate manifestation of the evil side).

And I really like the way his story ends, with the tormented doctor hurling himself off a cliff to prevent himself from hurting any of the people he cares about. After seeing the X-Men battle him for two entire issues, his conflicted humanity becomes an emotional knife twist for readers instead of the typical “we beat the bad guy” ending. I love those types of endings (obviously, this isn’t the end of ol’ Sauron).

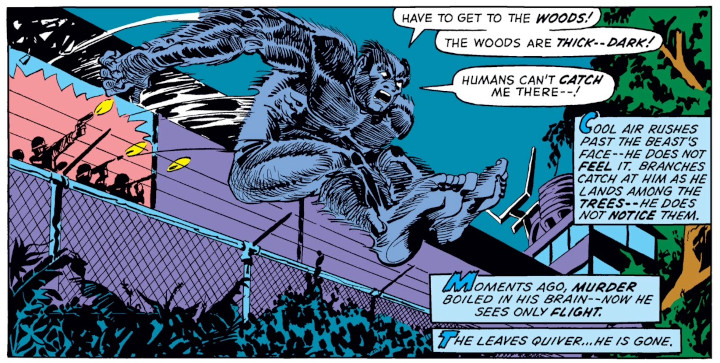

And I have to say, the brilliant Neal Adams takes over as artist at the perfect moment (in issue #56). Not only are his layouts a refreshing change of pace from the mostly rectangle boxes that precede them, but he gets to draw the very first issue in which Havok wears his costume — which is the coolest looking costume in this entire run. The effect on his chest when he activates his power is a nice touch.

I’ve written so much about the good that it probably seems like I really liked this run. I must clarify that, overall, it’s pretty bad. The series hinges a lot of its action around fighting bad guys while everyone is shouting out exactly what they’re doing in each panel (“My ice blast will slip you up, turning an ordinary puddle into a slippery trap!”)

We also see a lot of crossovers where the X-Men face off against the Fantastic Four, or the Avengers, or Spider-Man, simply because of some misunderstanding that arises between them (which inevitably is solved the moment anyone is able to actually explain themselves). This sort of writing is nothing more than an excuse to see who’d “win” in a fight between two popular characters, and it always feels more like a kid playing with action figures than a serious writer trying to figure out how these characters would actually act. I hate that stuff so much.

There’s also a point at which the X-Men literally fight Frankenstein’s monster (issue #40), and there’s one point where Bobby (Iceman) makes an offhand comment about how women shouldn’t be allowed to vote. A lot of this stuff hasn’t aged well at all.

But Neal Adams’ art really does make the last section of it bearable (just as it’s becoming almost overwhelmingly tiresome), and there are a few decent stories amidst all the uninspired schlock. I’m glad I read it, but I certainly wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who’s trying to figure out how to get into the X-Men (my starting-point recommendations are generally either Claremont’s run, Grant Morrison’s run, or Jonathan Hickman’s run, as all three of those are decent places to jump into the story without needing to consume overwhelming amounts of previous lore).

Uncanny X-Men reading order

Here’s the mapping that got me through Uncanny X-Men 1-66 (I should point out that it wasn’t yet called Uncanny when these issues were first printed, but this series is often retroactively referred to as Uncanny X-Men to avoid confusion with other X-titles):

- Uncanny X-Men (1963) – #1-5

- Fantastic Four (1961) – #27-28

- Uncanny X-Men (1963) – #6-39

- X-Men: First Class (2006) #1-8

- Avengers (1963) – #47-49

- Uncanny X-Men (1963) – #40-45

- Avengers (1963) – #53

- Uncanny X-Men (1963) – #46-48

- Doctor Strange (1968) – #182

- Ka-Zar (1970) – #2-3

Note: Marvel Tales #30 should go right here, but I wasn’t able to find it. This would conclude Angel’s Ka-Zar story, which seems like a somewhat important arc for his character.

- Uncanny X-Men (1963) – #49-66

- Fantastic Four (1961) #102-104

This took me from the very beginning of the X-Men right up until the series was cancelled in 1970. (The issues of Fantastic Four at the end of this list show what happens to Magneto after X-Men issue #63. I originally read it there, but it’s kind of weird that the events of this arc wouldn’t be noticed or commented on by the X-Men. It makes more sense if you read it after the cancellation of the series.)

What’s next?

My next task is to read all of the X-Men appearances in non-X books that happened between 1970 and 1975 (the “Hidden Years” period). I’ll mostly be following the reading order established by It’s Always Darkest Before the Dawn, but I have some additional issues I’ll be tossing into the mix.

If you want to read that full review (along with the reading order), you can check out my “Hidden Years” review.

Hello Josh, I would also like to read the older X-Men comics. Ideally from the beginning up to the 80s stuff. But I don’t how to read them, due to the high prices and availability of such material.

What are the resources that would help me find them? Free scans? Cheap reprints and/or TPBs?

Any help will be appreciated.

If you’re good with digital, your best resource is Marvel Unlimited. It’s ten bucks a month, and it lets you read as many back issues as you want. Plus, there’s a free trial, so you can test it out if you’re not sure you’ll like it. I personally have some issues with MU, but it’s a pretty cheap way to read old Marvel stuff.

For the 1960s in physical format, a halfway decent option is the omnibuses, which collect the full original run in two massive volumes. The first volume sells for around $60, while the second one sells for around $75. Here’s a link to the second one:

https://cheapgraphicnovels.com/x-men-omnibus-vol-02-hc-cassaday-cvr-new-ptg.html

Unfortunately, the first one is out of stock at Cheap Graphic Novels, but you might still be able to snag it at Amazon.

I’ve collected almost all of Chris Claremont’s 17-year run in omnibus format, and it’s not a cheap way of reading this content, but it’s my personal favorite. Just watch your wallet if you start collecting omnis, because it’s a real money-sink.

Another physical option is the Epic Collection line. Those are full-color paperbacks, and they collect a good chunk of the early years. However, those go in and out of print, and whenever a volume goes out of print, it gets ludicrously expensive. In fact, if you’re JUST looking to collect the 1960s, the omnibuses might end up being cheaper in the long run, since there are only two volumes and you can get the full series for about $135.

If you want to skip the 1960s and 1970s, though, this is a really good starting point:

https://lightgungalaxy.com/2022/05/15/uncanny-x-men-vol-3-chris-claremont-omnibus-review-and-reading-order/

Personally, I think this is the absolute best of the 1980s X-Men, and it’s better than absolutely anything from the 1960s or 1970s. It’s also not SUPER back-referential, though it will definitely reference major events like the Dark Phoenix Saga, etc. Still, this is a pretty decent jumping-on point if you’re specifically interested in the 1980s.

Frankly, I don’t understand your disdain for the “First Act” of the X-Men series. Just because the Iceman tossed off an innocent joke about women’s suffrage isn’t any reason to cop a ‘tude. Frankly, the Neal Adams period ( 1969 ) is, for me, the high-water mark of the entire series. All these stories, from issues #56 to 65, are cinematic in their scope. That’s industry-lingo for ‘big-screen movies can be made from these stories.’ They also benefit from a glaring lack of political correctness and social commentary which plagued the Claremont run. The Original X-Men possess a charm that has been lacking from most later iterations. Twenty-three/twenty-two years ago, John Byrne revisited this period in what was obviously a dream-project for him called “X-Men: The Hidden Years”, which did a masterful and seamless job of recapturing the magic and charm of the Adams year. If ‘X-Men’ 1969 had never happened, ‘X-Men’ 1975-to-present wouldn’t have happened, either. Character-for-character, I will take the Original X-Men over any other team line-up, any day of the week. The Original X-Men ROCK!!!

The Neal Adams run is definitely the best part of the 1960s run (with the exception of “The Origin of Professor X”, which is still my favorite issue from this entire decade). But this line from my review pretty much illustrates my feelings about the 1960s era:

Yeah, Bobby throws out an offhand line about voting rights, but I only pointed that out to emphasize how poorly this material has aged. It didn’t affect my opinion all that much, and you could easily argue that he was the youngest member of the team and was simply acting immaturely in that moment, or that he was just making an offhand joke that was in bad taste. It does feel oddly out of character for him, though, as I can’t think of another moment in the entire series where he expresses anything even close to that.

I think Claremont’s work in the 1970s is revolutionary but hasn’t aged all that well, but his work in the 1980s is peak X-Men for me. I think 1983ish is a particularly strong era, and 1987ish is another high point of the series.

But different strokes for different folks. I started reading comics in the 1980s, so it’s possible that nostalgia has clouded my perception and placed this decade on a pedestal. But, I mean, I’ve been re-reading a lot of 1980s X-Men lately (I just finished Mutant Massacre) and I absolutely love it.

Ultimately, I think it’s great that people still read 1960s X-Men, and it’s great that there are people who still love it. It’s not my cuppa, but folks are allowed to love it.